The Fed’s third consecutive rate cut heralds global policy divergence, and a new market dynamics emerge from the power struggle between Europe and Japan

- December 11, 2025

- Posted by: ACE Markets

- Category: Financial News

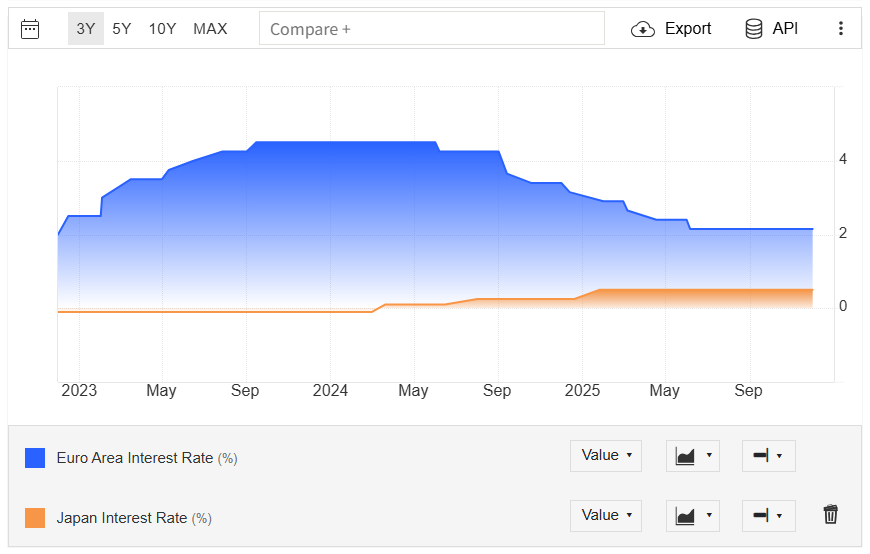

On December 11, 2025, the Federal Reserve pressed the “start button” for interest rate cuts for the third consecutive time, lowering the benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points to 3.50%-3.75%. This “easing anchor” did not trigger a synchronized move by central banks around the world; instead, it sharply contrasted with the European Central Bank’s “holding steady” and the Bank of Japan’s “rate hike countdown.” The divergence in monetary policies among the three major economies is not an isolated event, but rather an inevitable result of mutual influence and constraint within the interconnected framework of global capital flows, exchange rate games, and inflation transmission, collectively outlining the core game landscape of the global financial market in 2026.

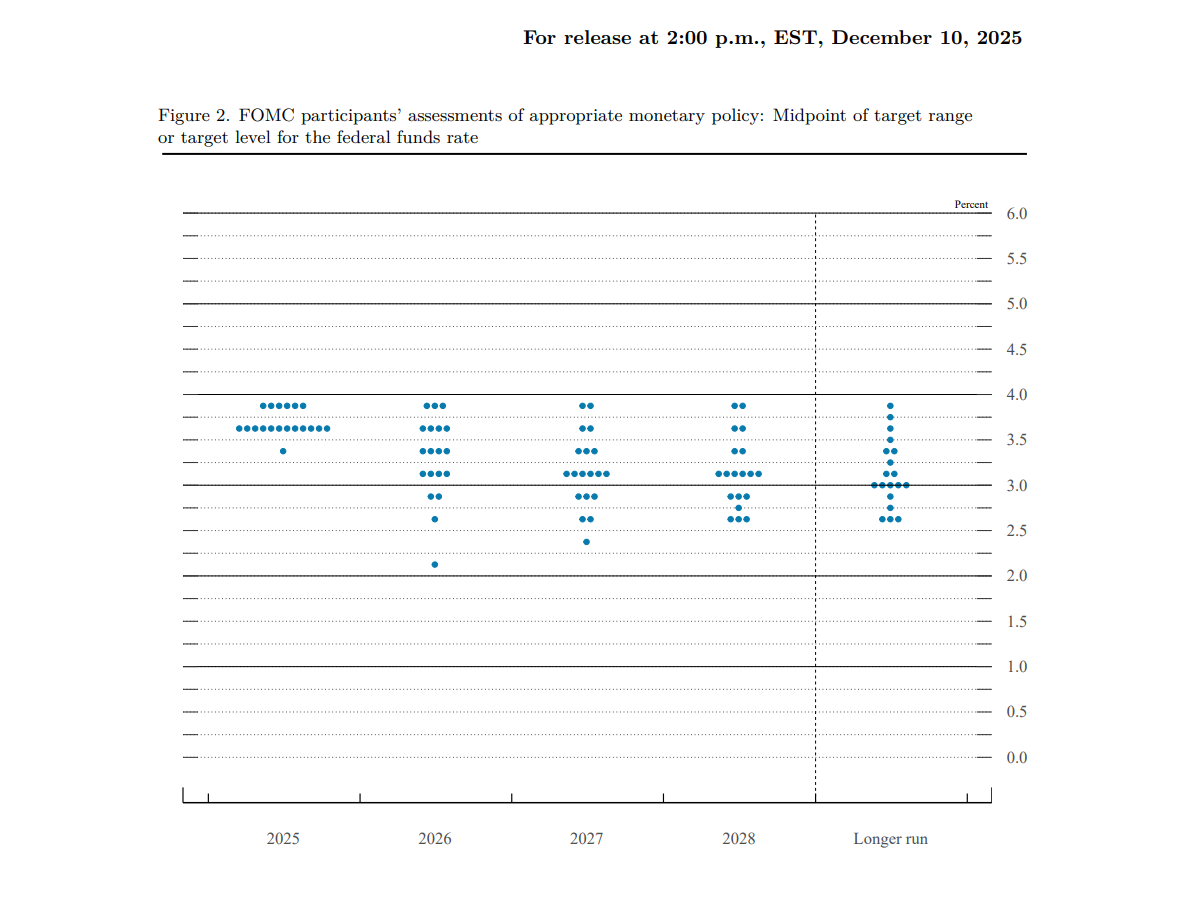

The core logic behind the Federal Reserve’s rate cuts is to address the “moderate expansion but emerging risks” in the economy: a balance between slowing employment, rising unemployment, and high inflation necessitates a “gradual easing” approach. This is complemented by a $30 billion Treasury bill purchase program and a reduction in the reserve requirement ratio to 3.65% to ensure policy transmission. The dot plot maintains its forecast of a 25 basis point rate cut in 2026, clearly defining the boundaries of “no excessive monetary easing” and constraining the policy choices of the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan. The 9-3 vote (1 vote for a 50 basis point cut, 2 against) highlights the central bank’s dilemma of “balancing domestic risks and cross-border spillovers” amidst sticky inflation and uneven recovery. As a global liquidity anchor, the Fed’s easing weakens the dollar’s interest rate advantage, causing funds to shift to higher-yield assets. This is a key external factor driving the European Central Bank to maintain its interest rates and the Bank of Japan to consider raising rates.

Europe refuses to follow easing policies, while Japan takes advantage of the situation to raise interest rates.

The European Central Bank (ECB) did not follow the Federal Reserve in cutting interest rates, primarily due to fundamental differences: the upward revision of third-quarter GDP confirmed that economic risks were manageable, and inflation was approaching the 2% target in the medium term, thus eliminating the need for interest rate cuts. A deeper logic was to avoid narrowing interest rate differentials triggering capital outflows and weakening the euro’s stability. Therefore, ECB Governing Council member Simkus shifted to a “no need for rate cuts” stance, while Schnabel tacitly approved of rate hike expectations, maintaining the attractiveness of interest rate differentials by releasing hawkish signals. Although there were internal disagreements (Villeroy denied a short-term rate hike), “no rate cuts” had become a consensus, forming a strategy of “waiting and seeing” to hedge against the Fed’s spillover effects and stabilize inflation.

The Federal Reserve’s easing measures have created a window of opportunity for the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to raise interest rates: Previously, the yen had depreciated by over 10% due to the inverted yield curve between Japan and the US. The Fed’s rate cuts have weakened the dollar’s interest rate advantage, and coupled with Japan’s core inflation approaching 2% and its economy withstanding the impact of tariffs, the BOJ has found an opportunity to normalize its policy. The market’s expectation for a BOJ rate hike on December 19th is 91%, with the rate projected to rise from 0.5% to 0.75% (a 30-year high). The rate hike targets two main objectives: narrowing the Japan-US interest rate differential to curb yen depreciation and alleviate import inflation; and curbing soaring government bond yields (10-year yields approaching 2%, with long-term yields hitting record highs) to prevent the bond market from spiraling out of control. Furthermore, the issuance of $75 billion in new Japanese bonds, which would have created supply pressure, has been offset by the Fed’s bond purchases increasing global demand for safe-haven assets, providing a liquidity buffer for Japanese bond issuance and indirectly reducing resistance to a rate hike.

The core transmission of policy linkages: capital flows and asset pricing restructuring

The policy divergence among the three central banks is not isolated, but rather forms a closed loop through capital flows, exchange rate linkages, and inflation transmission, profoundly altering the logic of global asset pricing.

Currency market: Interest rate differentials drive currency strength divergence.

The Federal Reserve’s rate cuts have diminished the dollar’s appeal, making the yen the biggest beneficiary. The expectation of a Bank of Japan rate hike and the Fed’s easing have created a “narrowing interest rate differential,” driving the yen’s strength against the dollar since last week. The euro, on the other hand, has been supported by the ECB’s “no rate cut” stance. Although it has fluctuated due to internal policy disagreements, its overall resilience has significantly increased. This currency divergence is not one-way but rather mutually constraining: a stronger yen may force the ECB to maintain a hawkish stance to prevent a relative depreciation of the euro; conversely, excessive dollar weakness could trigger concerns from the Fed about a rebound in inflation, limiting further rate cuts.

Bond Market: Global Interest Rate Spread Pattern Recalibrated.

The Federal Reserve’s purchase of short-term Treasury bills directly suppressed short-term yields on US Treasuries, while expectations of a moderate interest rate cut in 2026 limited the rise in long-term yields. Japanese government bond yields continued to climb due to expectations of interest rate hikes, but ample global liquidity resulting from the Fed’s easing measures partially absorbed the pressure from new Japanese bond supply. Eurozone government bond yields, supported by expectations of no interest rate cuts, remained relatively high. The combined effect of these three factors has created a new pattern in the global bond market: a downward trend in US Treasury yields, increased volatility in Japanese bonds, and high-level fluctuations in European bonds. The restructuring of arbitrage opportunities has triggered a reallocation of cross-border capital.

Risky assets: Supported by both ample liquidity and policy certainty.

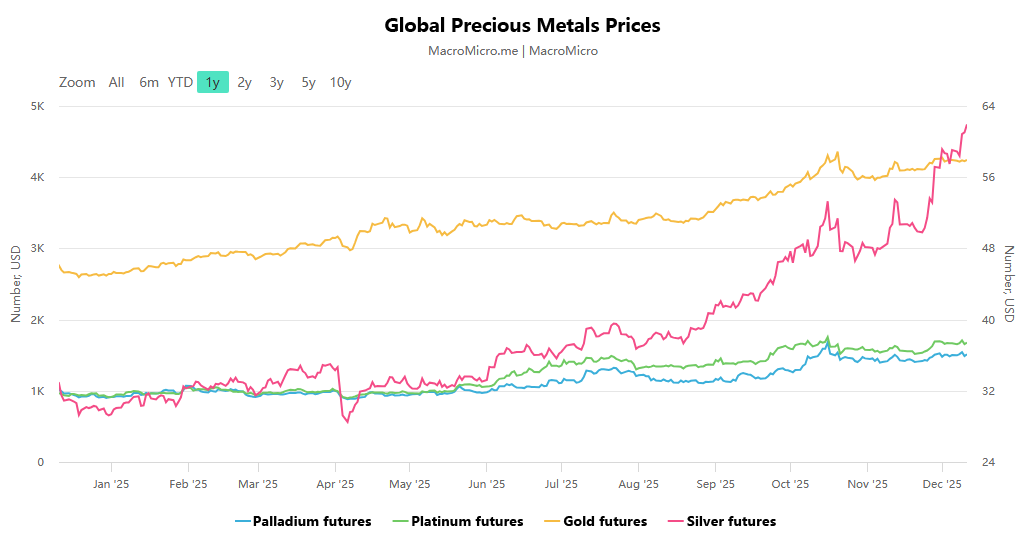

The Federal Reserve’s easing policies have provided a liquidity base for global risk assets, while the policy clarity of the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan (the ECB will not cut interest rates, and the Bank of Japan is likely to raise rates) has reduced market uncertainty, driving funds to concentrate on assets that offer both returns and safety. Previously, precious metals such as silver, which had been facing supply-demand imbalances, saw their upward momentum further strengthened against the backdrop of the Fed’s rate cuts lowering real interest rates, coupled with global capital seeking safe havens and value appreciation. The stock market presented structural opportunities, with a weaker dollar benefiting emerging market equities, while European and Japanese equities benefited from stable domestic policies and improved economic fundamentals.

The Future of Game Theory and Collaboration Amidst Continued Differentiation

The policy paths of the three major central banks in 2026 are clear: the Federal Reserve will maintain “gradual easing,” with inflation stickiness or recession risks influencing the magnitude of rate cuts; the European Central Bank will maintain interest rate stability, with its rate hike tendency depending on marginal changes in inflation and economic data; and the Bank of Japan will enter a period of observation after its rate hike, with subsequent adjustments anchored to the yen, government bond yields, and inflation balance. It is important to clarify that this policy divergence is not a “zero-sum game,” but rather a “dynamic coordination” within the context of global economic interdependence: the Federal Reserve needs to pay attention to the impact of European and Japanese policies on the dollar and capital flows, while Europe and Japan need to avoid market volatility caused by excessive divergence. For investors, grasping three key logics can balance risk and return: the liquidity dividend from the Federal Reserve’s easing, the currency spread opportunities driven by policy divergence, and the structural asset market opportunities arising from capital reallocation.

Overall, the Federal Reserve’s three consecutive rate cuts are not only a policy adjustment within the United States, but also a catalyst for the divergence in global monetary policies. The differentiated responses from the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan are essentially rational choices made by various countries based on their own fundamentals in the context of a multipolar global economy. This pattern of “core easing + peripheral hedging” will continue to dominate global financial markets in 2026, and the transmission effects and room for maneuver in policy linkages will be the core source of future market opportunities and risks.